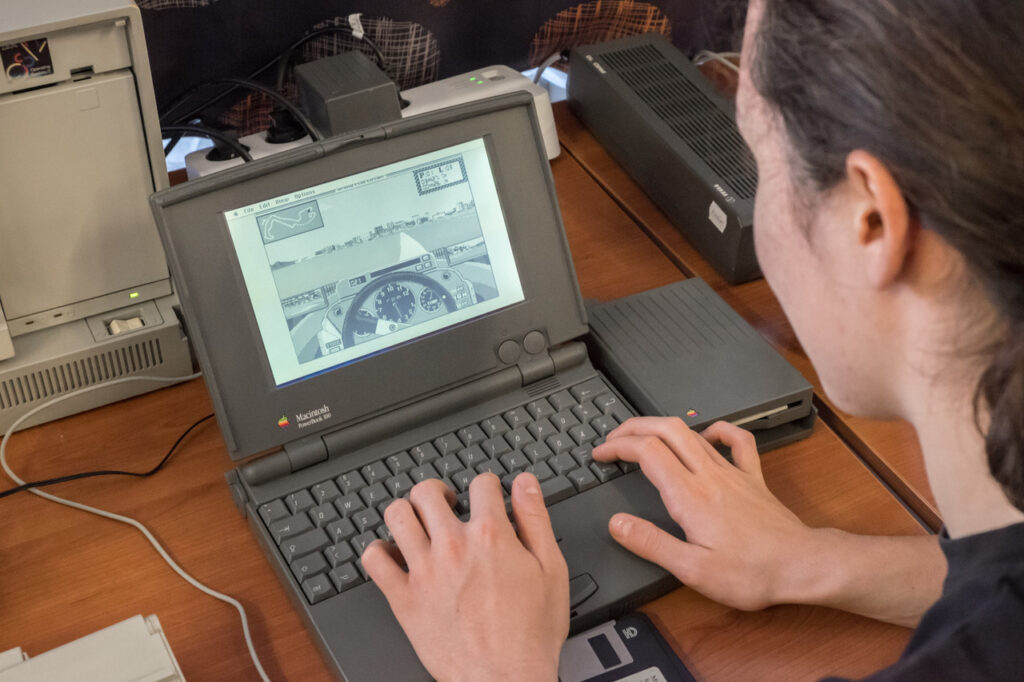

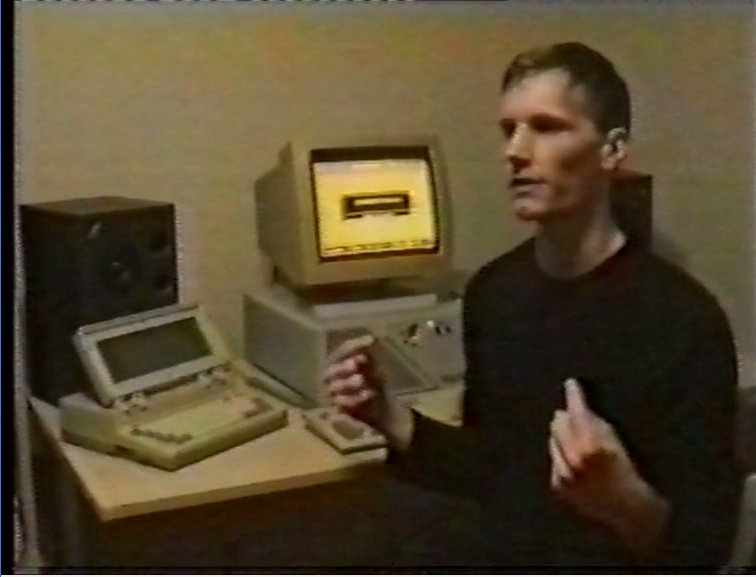

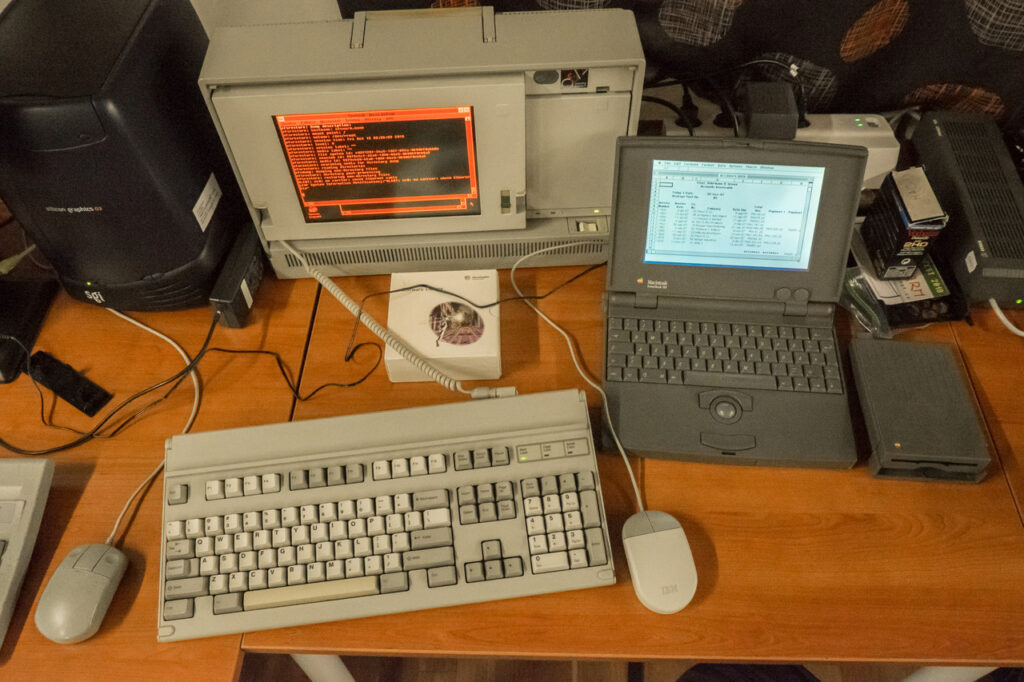

Final step in PowerBook 100 restoration

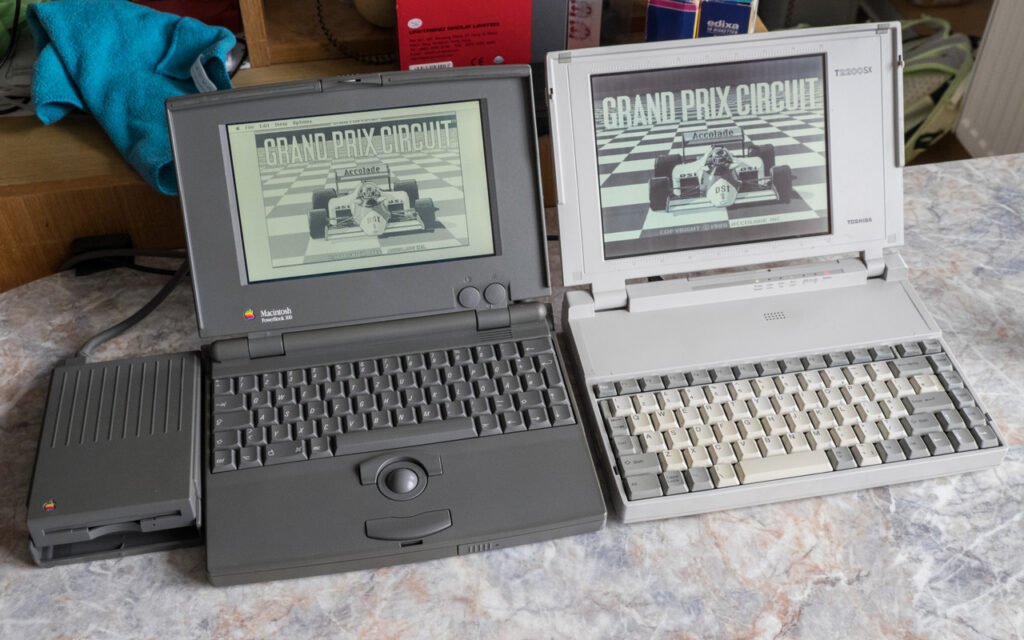

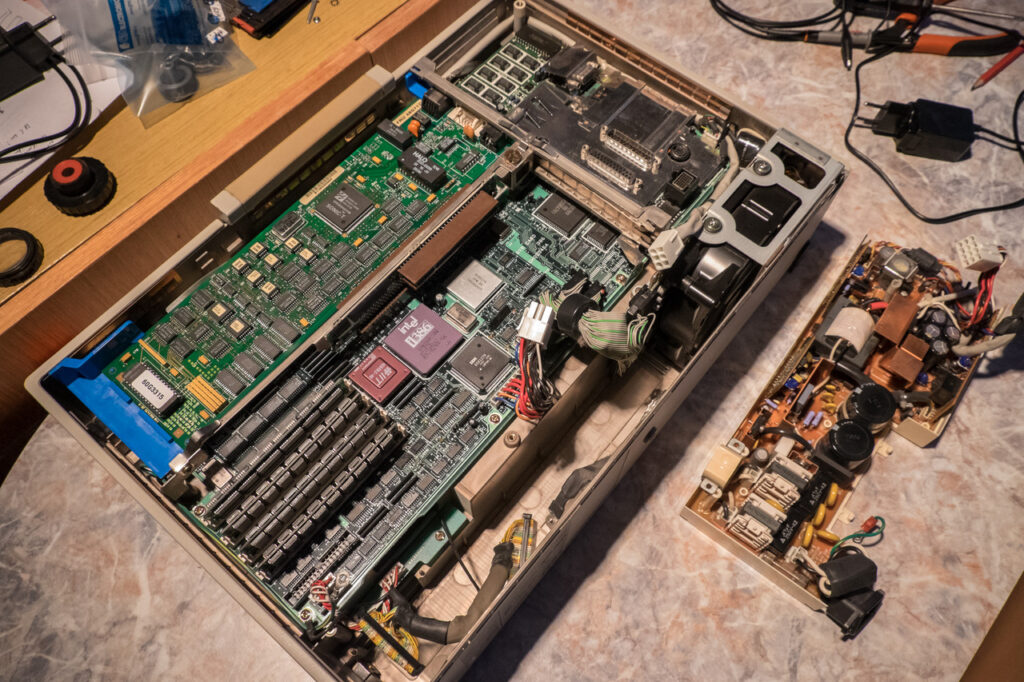

Although I’m not a collector, I always wanted to have one PowerBook 100 just to remind my childhood. It was the coolest Apple notebook from the early 90s. Last year, we brought back to life two out of three dead PowerBooks 100 from a friend of mine, so we could keep one for free. The restoration was not finished though. All the 2.5-inch Conner SCSI hard drives were dead.

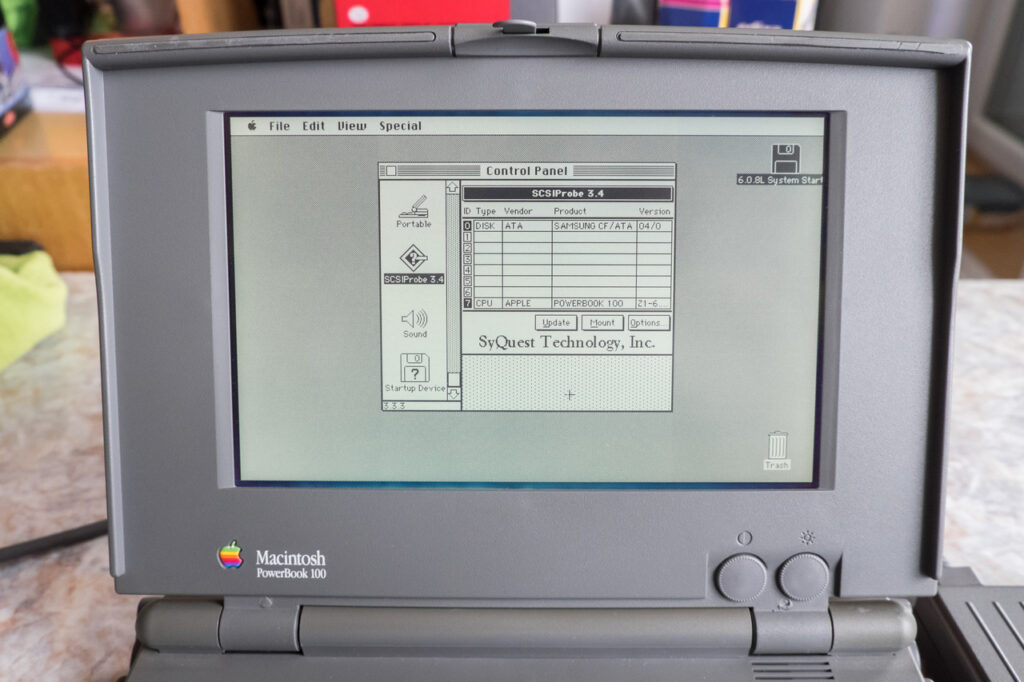

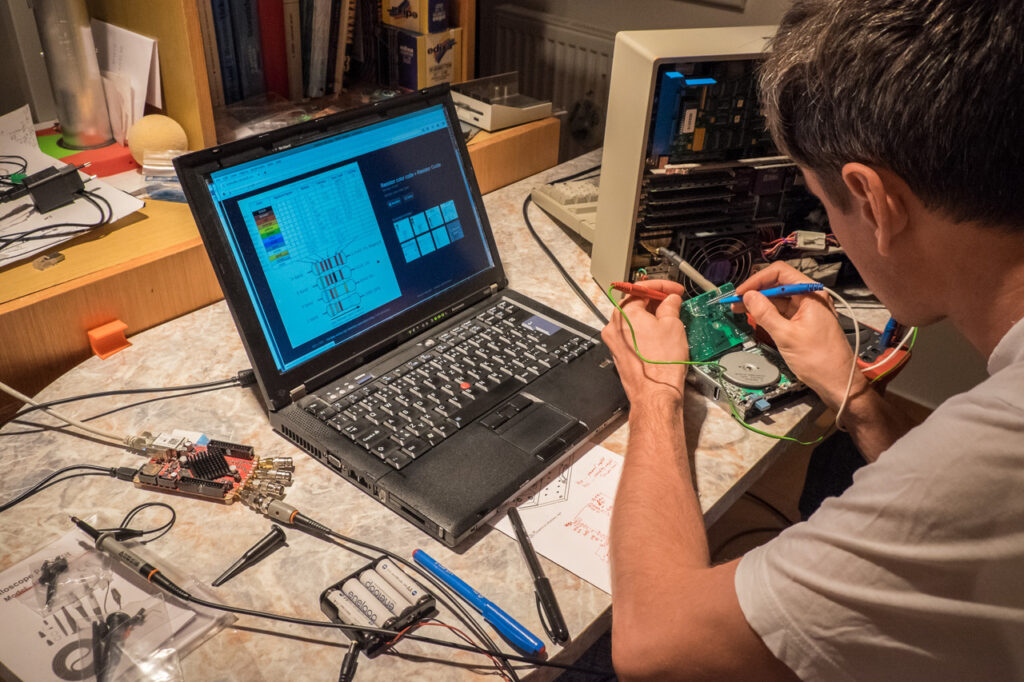

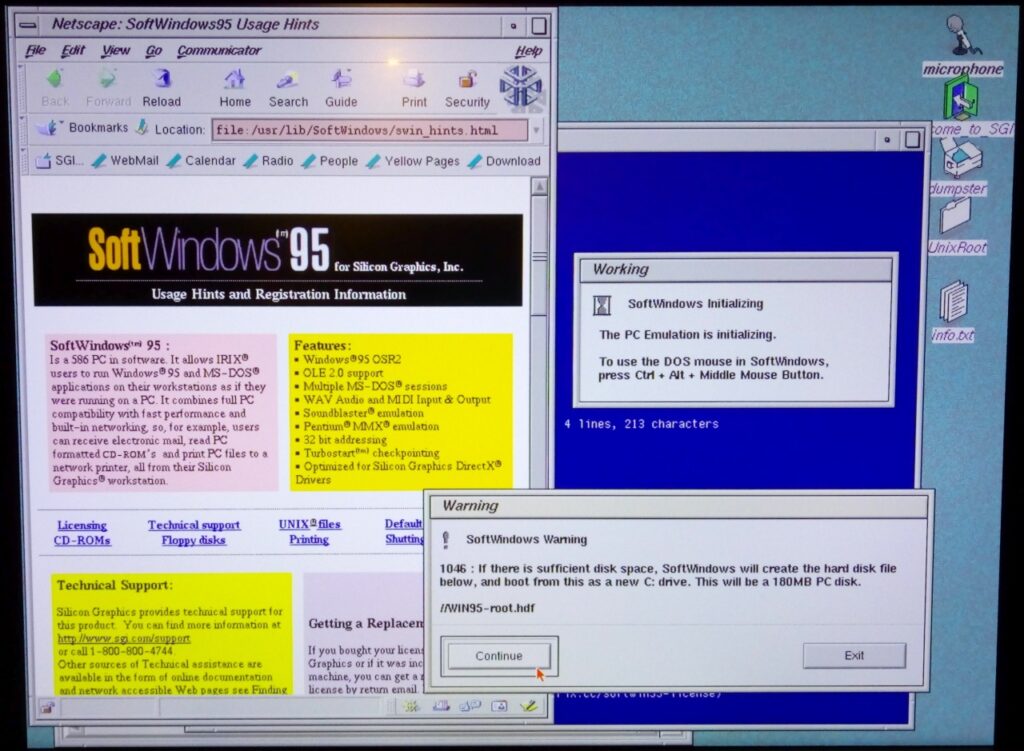

These drives are hard to find so I installed the PowerMonster II adapter last weekend. I would do it maybe half a year ago but the first experiment was with a 2GB CF card and resulted in the “SCSI Bus Not Terminated” error. I was later told that old SCSI Mac don’t like large hard drives. With a 512MB CF card, the system immediately detected a new drive on the bus.

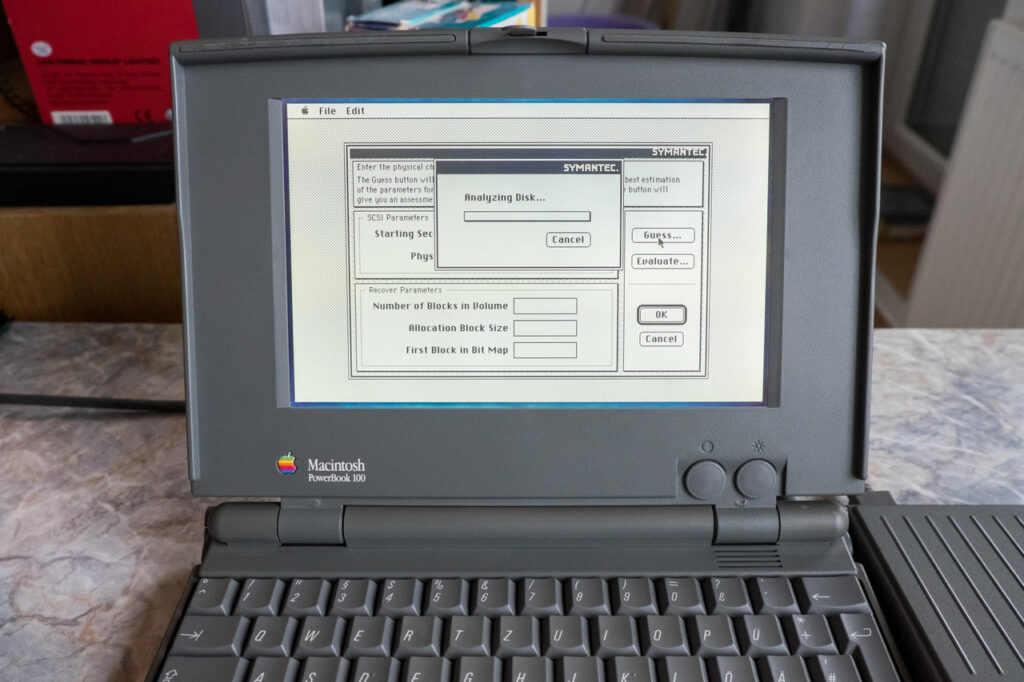

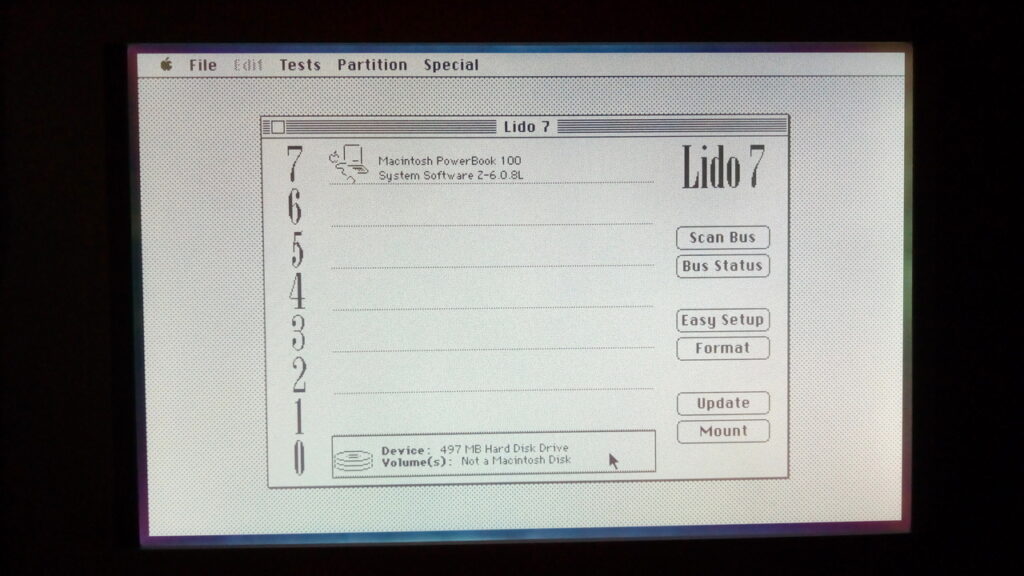

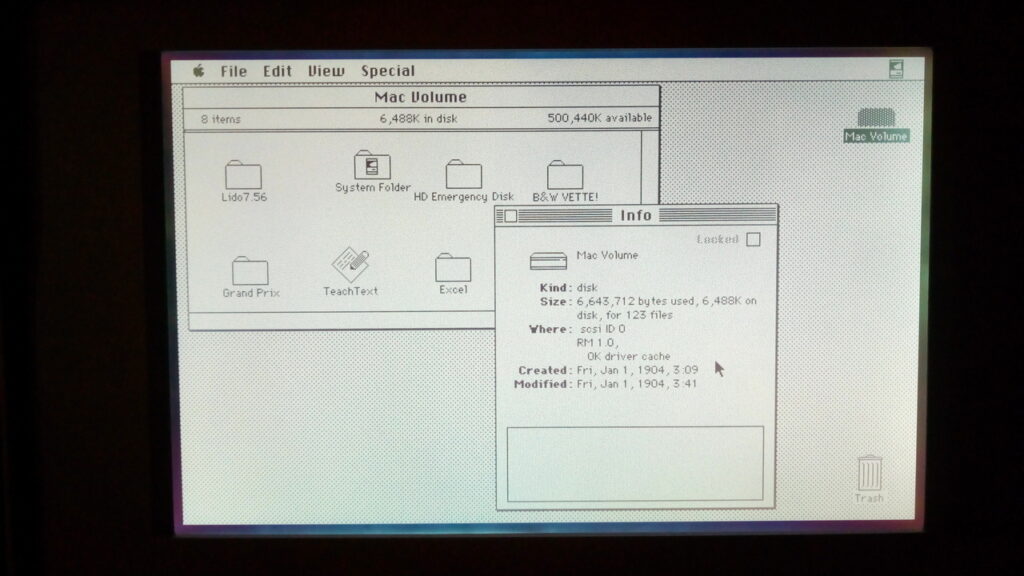

Making it usable with Mac was a different story. OS installer diskettes contain an utility for hard drive setup but it refuses to work with non-Apple drives. I tried even “hacked” versions that should work with other drives but with no success. Finally, after trying multiple utilities, Lido 7 rescued me five minutes before I wanted to give it up. I clicked on “Easy Setup”, set a name and icon for the drive and everything was ready to install the operating system.

Unlike DOS and UNIX systems, old Macs never had universal utilities to set up any third-party hardware. I don’t like that approach but Apple had that as a part of its strategy.