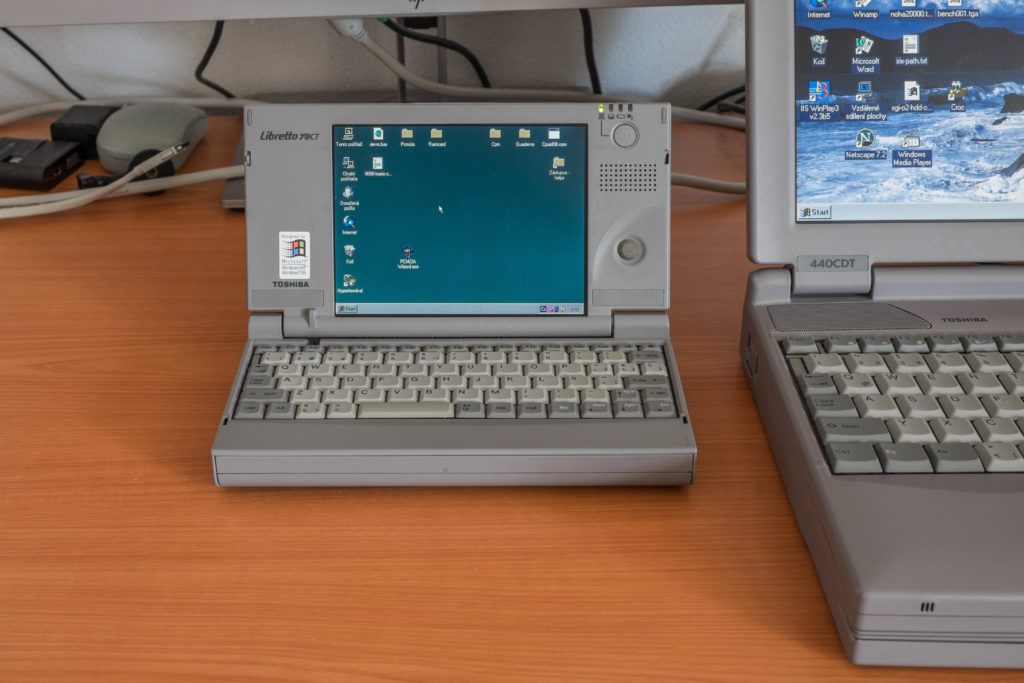

Tiny laptops appeared on the market immediately once it was technically possible to made them. Among the firsts, there was PC XT-compatible handheld Poqet PC introduced in 1989. It took just eight years to miniaturize the original IBM PC to the level that you can put it in a (large) pocket. These devices together with HP 95/100/200lx and others were IBM PC compatible, but had just simple non-backlit monochrome screens and no hard drives. Toshiba Libretto, on the other side, came with components similar to bigger laptops. The 70CT model was introduced in 1997 and cost just $2000, so it was even cheaper than standard-size laptops (especially if we consider only configurations with active-matrix TFT displays).

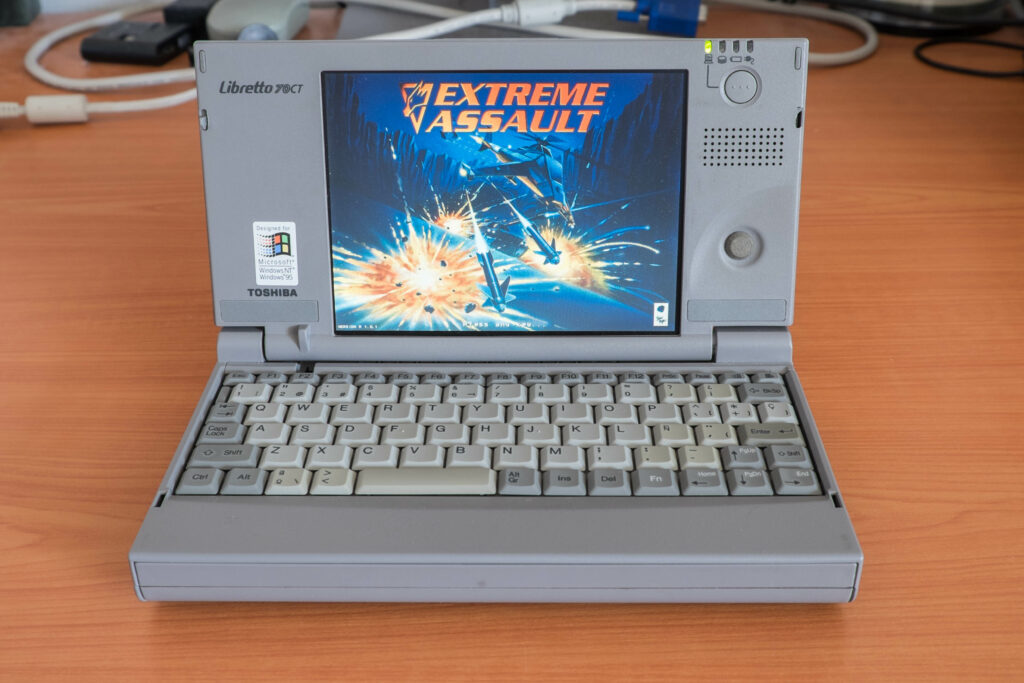

Libretto was a device for a very specific type of users. Although its performance was not much behind standard laptops, the tiny keyboard was not suitable for office work. Together with a 6.1” display (640×480), Libretto was not able to provide the full ergonomics of standard laptops.

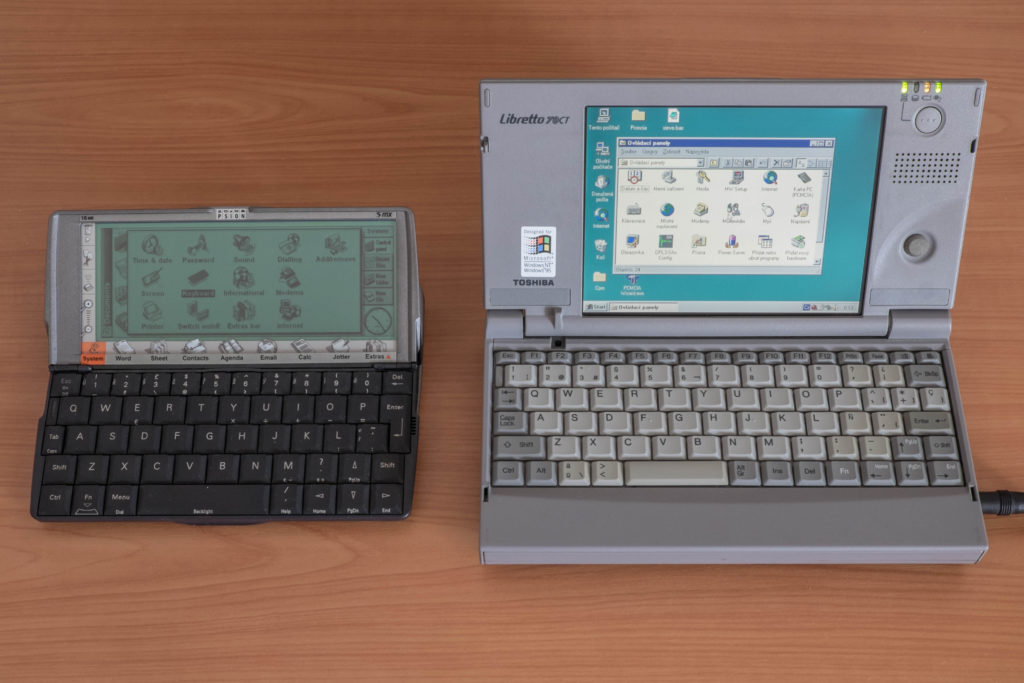

If you think of it as a handheld for taking notes and creating simple spreadsheets, this was not the best choice either. There were handhelds like PSION Series 5, with weight just 354g (compared to Libretto’s 850g) and price only $699 (the 8MB version). PSION supported instant on and allowed up to 40 hours of use on two AAA batteries (compared to Libretto’s two to three hours using a Li-Ion battery pack). On the other side, if you wanted to interact with PCs, you needed to convert every document to a different format.

Libretto was for those, who needed to run PC programs on the go and the computer was not their primary tool, so they didn’t want to carry a heavy device in their briefcase. If one’s computer usage was more about putting a few numbers in an already created spreadsheet on a customer site, using expert system programs outside office or diagnosing industrial devices over serial port, Libretto could suit the needs perfectly. You could run any DOS or Windows program on a device that could be operated as a handheld. That was a big thing back then.

Hardware design trade-offs

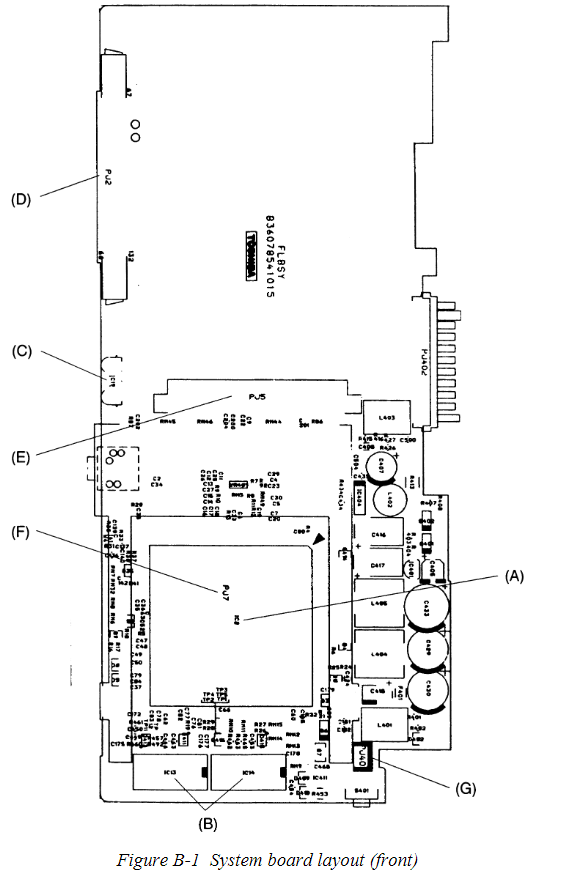

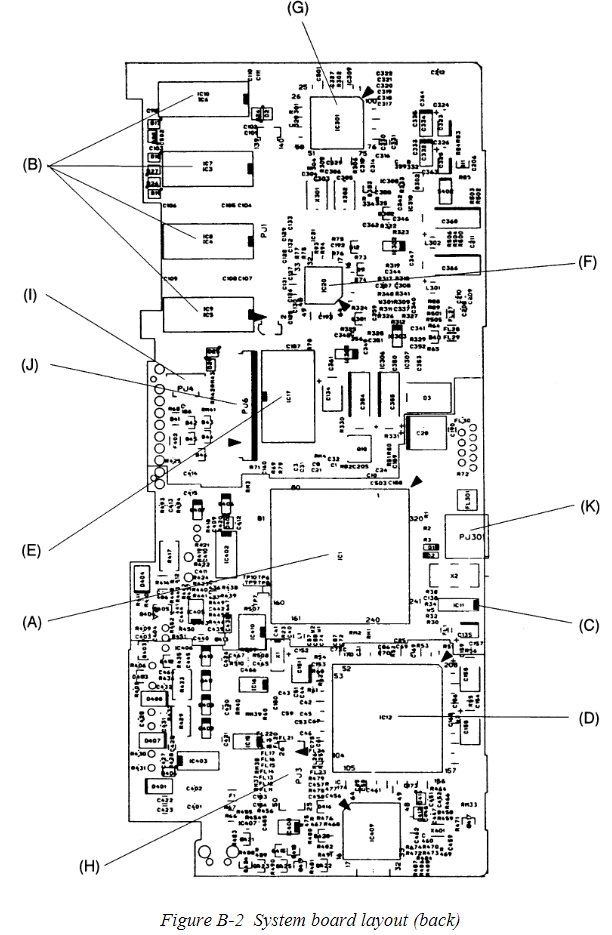

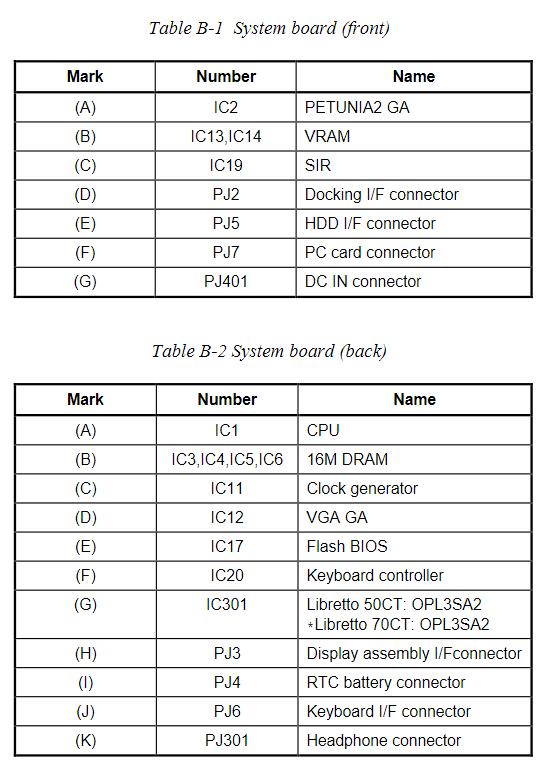

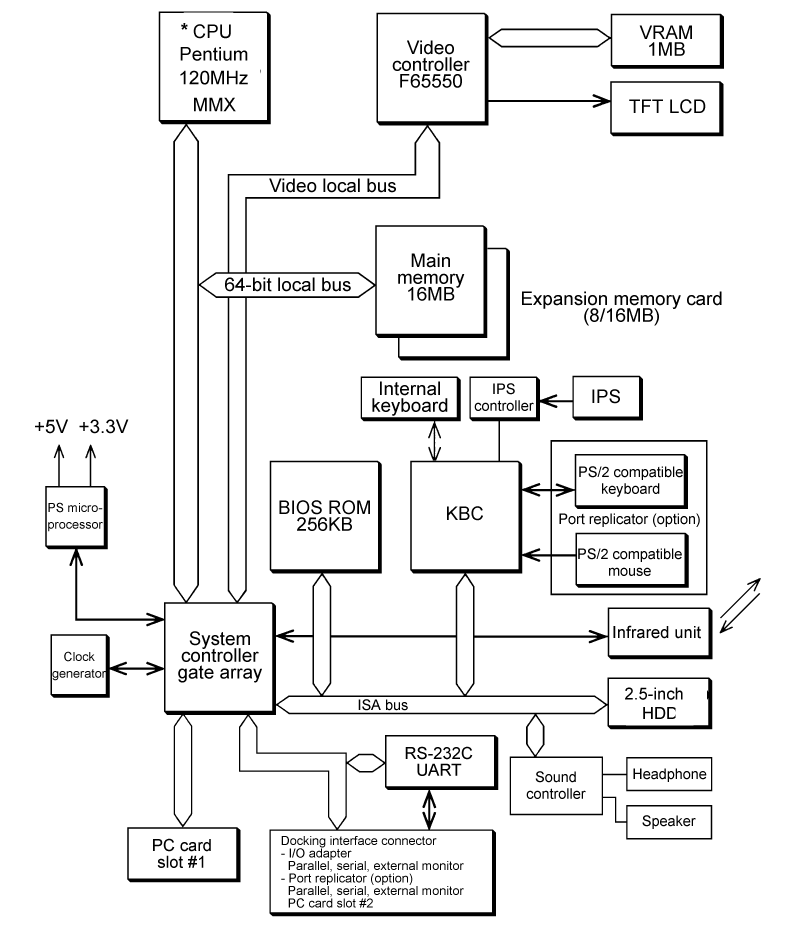

Putting a 120-MHz Pentium MMX, up to 32MB RAM, a standard 1.6GB 2.5” HDD, sound support and one PCMCIA slot in such a small package could not be done without several trade-offs. The key was to integrate most functions into a single gate array chip – this one is called Petunia2 and it is the largest chip on the mainboard (larger than the CPU). It integrates everything except audio (Yamaha OPL3-SAx), a keyboard controller, BIOS flash ROM, a graphics controller and RAM.

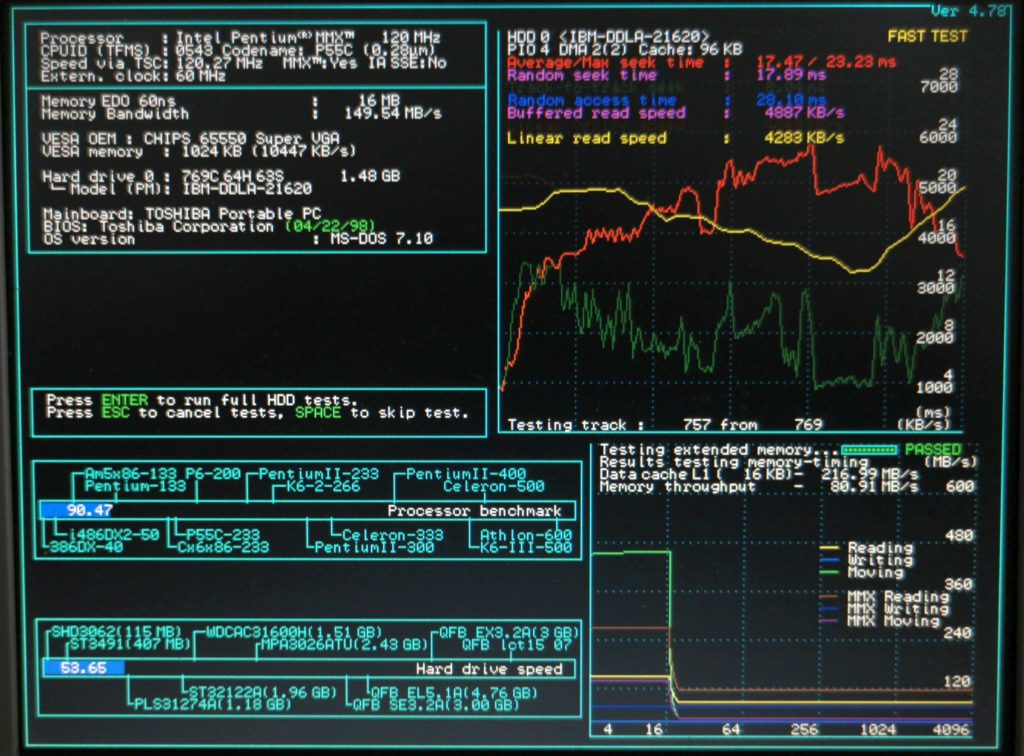

A standard mobile Intel Pentium MMX processor is connected directly to the Petunia2 and 64-bit memory. 16MB of RAM is integrated on-board and up to 16MB can be added using a special module. Here we have the first drawback – there is no L2 cache. Until Pentium II (and Pro), Intel CPUs had L2 cache on the mainboard. Omitting the L2 cache saved space on the mainboard and decreased total power consumption. As a result, programs that rely heavily on large cache can be even 30% slower compared to laptops with the same CPU and 256KB of L2 cache (typically software-rendered 3D games with textures).

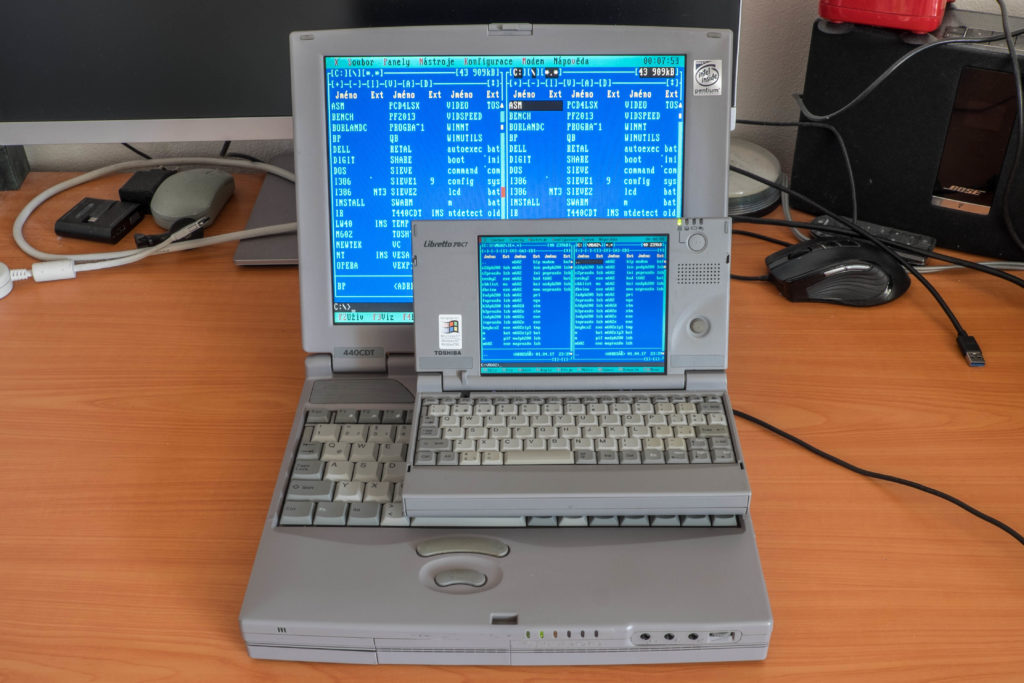

Libretto is not very fast even in the RAM access. It provides 25% slower reads and 40% slower writes compared to a Toshiba Satellite 440CDT (133-MHz Pentium MMX; 66MHz FSB instead of Libretto’s 60MHz). I should add that the 440CDT is not a RAM-access speed demon either. Hi-end laptops with Intel 430 chipsets can provide 30% more performance compared to the 440CDT results.

Given the slow RAM and missing L2 cache, there is a huge benefit from using the Pentium MMX CPU instead of the original non-MMX one (used in Libretto 50CT). Even if you don’t run a program that can leverage MMX instructions, every MMX CPU has twice as big L1 cache (32KB instead of 16) and that helps almost everywhere.

Additional notes: Unlike desktop computers, most (standard-size) 486 laptops did not have L2 cache. That started to change with early Pentium models, but only the more expensive ones. Cheap laptops did not have L2 cache until 1997-1998.

Local Bus video, no PCI

There was not enough space in the Petunia2 for a fully fledged PCI bus that started to appear in standard laptops during 1997, so most components are connected to a slow 16-bit 7.5-MHz ISA bus. The IDE (disk) controller suffers the most from this hardware decision. However, the biggest hard disk performance pain point of Libretto is caused by the lack of DMA support on the IDE controller side (integrated in the Petunia2). This does not matter much in DOS, but Windows 95 is significantly slower since CPU has to handle all disk accesses using PIO mode (PIO = Processor Input/Output) and it takes more time because of the slow bus. The hard drive is limited to speeds below 5MB/s.

The lack of PCI also means that the PC Card (“PCMCIA”) slot supports only 16-bit cards and not the 32-bit CardBus standard.

Using the ISA bus for a graphics controller would result in inadequate performance. You could partially hide the slow bus using a graphics controller that supported bit block transfers (BitBLT), so moving program windows in the video memory could be done without stressing the bus (but only as long as there is no desktop background picture behind them). On the other side, gaming and video playback performance would be bad anyway.

On 486 laptops, this was solved by connecting the graphics controller directly to the CPU local bus. The same mechanism was used even in desktops where you could find long VL-BUS slots (VL-BUS = VESA Local Bus; that was a standard defining control signals, the edge connector pinout and other things to ensure that local bus graphics cards are interchangeable). Old graphics chips often supported the VL-BUS together with direct 486 and even 386 CPU bus connections (these were different only in few details). The problem appears with Pentium CPUs which have a different local bus (64-bit instead of 32-bit). Although having VL-BUS slots in a Pentium-class desktop was a rare thing, early Pentium laptops often worked with graphics chips for the 486 local bus using a bridge chip. In case of Libretto, this bus-bridge functionality is again handled by the Petunia2 chip as you can see in the system block diagram:

Libretto 50CT/70CT has a HiQV32 (F65550) graphics controller from Chips & Technologies (the same chip that was used in Apple PowerBook 3400). Toshiba used Chips & Technologies graphics controllers in most of their laptop lineup back then. However, the larger models used the better version called HiQV64 (F65554) which differed in the 64-bit access to its own (video) memory. HiQV32 is a low-cost version that has just 32-bit video memory. These chips were not the graphics hi-end of 1997, but they were solid performers in the laptop segment. The chip supports not only BitBLT and raster ops acceleration, but also advanced video playback features like overlay, hardware scaler and YUV-to-RGB color space conversion.

If you think about the performance hit caused by using VL-Bus instead of PCI, there is none. These chips cannot fully utilize PCI bus and they provide almost identical results when it comes to copying between system memory and video memory. Wider memory bus for the video memory increases performance only when BitBLT is performed. I made a side-to-side comparison of both versions (HiQV32 vs. HiQV64) in Windows and the graphics performance difference was not noticeable. At the end, the biggest difference is in memory size – Libretto has just 1MB, a half of what larger models offered. Given the low resolution of the internal LCD (640×480), this is not a limiting factor unless you attach a large CRT. 1MB of memory means that a resolution of 1024×768 can be used with no more than 256 colors.

Using a Libretto

Toshiba Libretto became a valuable item for vintage hardware collectors. If you are looking for a good DOS gaming machine, I would recommend avoiding it. The keyboard is too small for proper gaming (or typing) and the point stick integrated in the lid will hurt your fingers if you try to play strategy games using it for more than 10 minutes. Also, the mono speaker offers far worse sound quality than larger Toshiba laptops of the era.

If you insist on using Libretto for DOS games, be prepared that it does not have Fn keys for changing sound volume and display brightness. Although the Yamaha OPL3-SA2 sound chip is initialized in BIOS and does not need drivers in DOS, I recommend installing a driver in order to have the access to a sound mixer (volume control for wave and MIDI). Regarding the display brightness, there is a DOS utility called TLCD.EXE that allows you to change brightness in four levels. This is especially useful when you operate the machine on battery (the default brightness for battery operation is the dimmest one, barely usable during a day).

The ports are very limited on this thing – the sound output is in the form of an uncommon 2.5mm jack and there is no VGA, PS/2 or serial interface directly on the device. You need a special port replicator, but beware – only the larger model has PS/2 ports. The simpler one has just a serial port, parallel port and VGA.

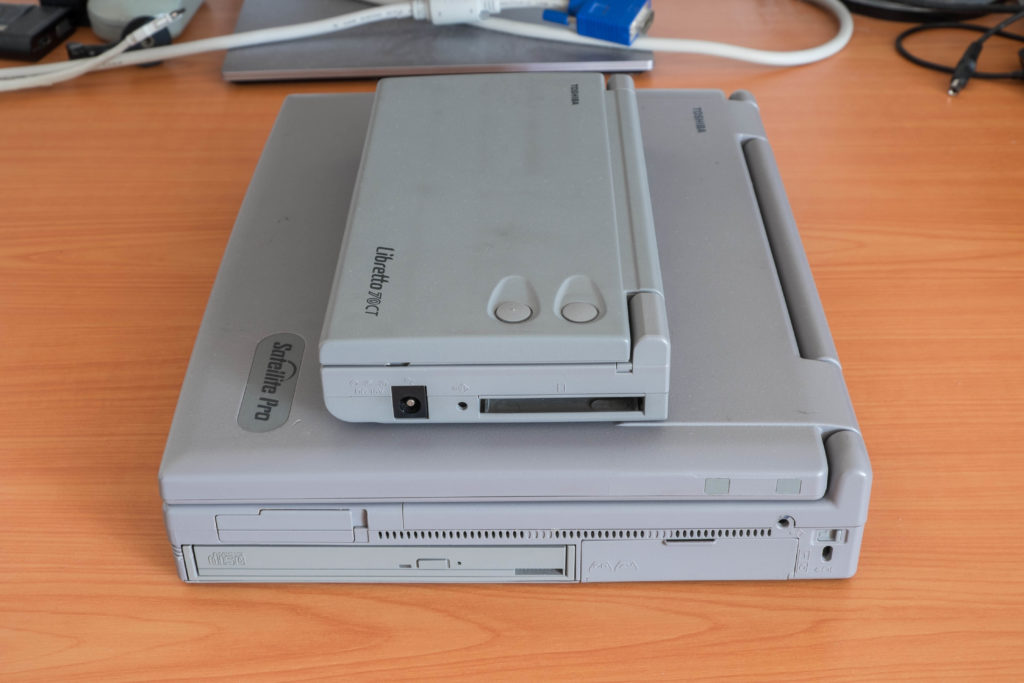

I mostly use this machine as a bridge to older computers. It can serve as a remote hard drive over null-modem cable (DOS/InterLink) or a serial terminal for old UNIX workstations. Thanks to PCMCIA, I can copy files to it over Ethernet or CF/SD cards. Many other laptops of the era can do the same things, but I like that Libretto does not take much space on my desk. It’s a perfect device for many service tasks related to vintage computers.

Technical specification

- CPU: 120-MHz Intel Pentium MMX (60-MHz FSB, 2x)

- RAM: 16MB on-board plus an empty proprietary slot

- Graphics controller: Chips & Technologies HiQV32 F65550 (1MB 32-bit memory, 32-bit VL-BUS, GUI acceleration, VESA 2.0 support)

- Internal bus: 16-bit ISA (7.5MHz) + 32-bit VL-Bus (30MHz)

- LCD: 6.1” active-matrix color TFT (VGA 640×480)

- HDD: 1.58GB 2.5” IDE (operated by an ISA EIDE controller with no DMA)

- Interfaces: audio (2.5mm), 1x PCMCIA Type II (16bit)

- Basic port replicator: RS232c, parallel port, VGA

- Wireless: SIR IrDA 1.0 (115Kb/s)

- Removable storage: external PCMCIA floppy disk drive (full BIOS support, so it is handled like a standard internal drive)

The graphics controller supports 640×480 in 24bpp (16 million colors), 800×800 in 16bpp (65 thousand colors) and 1024×768 in 8bpp (256 colors). It supports simultaneous using of LCD and CRT in fixed 640×480@60Hz. The highest supported refresh rate is 85Hz when the chip displays to CRT only.

Thanks for the article. Gives me some insight why my CF to IDE adapter still only gives 6-7MB/sec 🙂

Brutal análisis, de lo mejor que he leido sobre estas pequeñas laptops, yo tengo el 50ct y el 70ct y me encantan. Por cierto, he intentado buscar las dos aplicaciones para controlar el volumen y el brillo y no hay manera…¿podrías indicarme donde encontrarlas, por favor? Gracias por adelantado.

Thanks! DOS utilities for brightness change, LCD/CRT switch etc. can be found here: http://retro.timb.us/Systems/Toshiba_Libretto/LIBRETTO_DOS_UTILS.zip

Windows utilities should be still available from Toshiba (or how it is called today). For DOS sound (with mixer), it is necessary to find a DOS Yamaha OPL3-SA2 driver. I have it on my Libretto, but I am not at home (business trip). I will try to copy the installer from its HDD once I have the machine back in my hands.

I use my Libby 70CT to run DOS only. For Win98 I use my Libby 110CT. For WinXP I use my Libby U105. Yes I like them 🙂 !

Hello Everyone,

For those who may have an image disk of the original Hard disk with WIn95, that would be so great…

Try archive.org they have the OEM disk for 70CT in english.